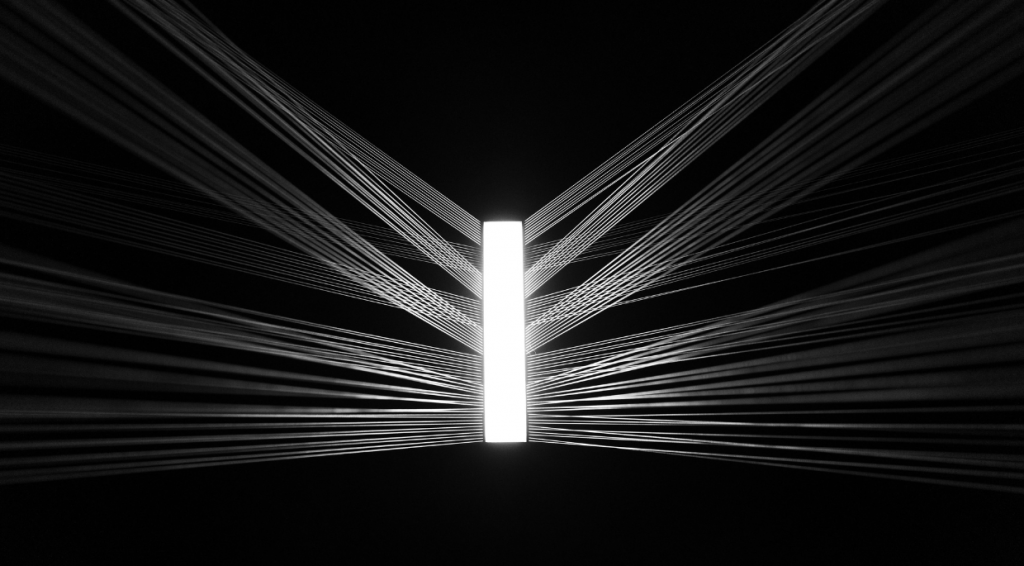

When it comes to his art, it is the ethereal that plays most to Muhannad Shono’s imagination. Originally an illustrator, the Saudi Arabian artist moved from ink drawings and self-publishing to making art as installations. His work, by his own definition, draws attention to a personal resolve and resistance against the real.

For Muhannad, the make-believe and the mythical have always mattered more, because they offered him a way out of the world. He positioned himself in the shadows of the perceived ‘truth’. Having gone on to represent Saudi Arabia at the Venice Biennale with the Teaching Tree, and having since been appointed as the Contemporary Art Curator for the 2025 Islamic Biennale, it is fair to say Muhannad has come out of his pictorial shadows to epitomise the energy and ambition of the new Kingdom.

I started by responding to attempts to restrict the imagination. So, in my early works, the line was being. I’d manifest characters and roles in my mind. I felt that there was a fear of the imagined world and this telling of a narrative at that time because it could change the lived world.

Growing up, in comics or illustrated books, the images would often be redacted and censored, and any book that I read would often appear as a weird confrontation/collaboration, between the censor and the original creator of the book. Even the ink that was used to obscure the image and the word only acted as a highlight, to draw my attention to everything that was missing. It trained or turned my imagination on, because I would often intervene upon what I couldn’t see to create more fluid readings, which stretched my imagination further.

Things started as pure illustrations, drawings that I could privately do alone, for which I could develop stories in my mind, create books, and self-publish. The idea of bringing to life both that world in the mind and turning it into something physical was really interesting to me.

It became about understanding the power of what you could formulate in your mind, and allowing that to become objects that could reshape, but also reform, the lived world. Considering how society thinks, gathers, congregates and behaves en masse, we naturally tend to assemble around narrative, and it becomes very important to fight for that space.

The space for narrative. In my work, I often usurp narrative, and take things that, let’s say, are engrained and familiar, such as mythology, and remix and reshape them to reclaim them and strip them of their original power. So, what is familiar to you, that you have heard this story before, here the characters and the outcome are entirely different

and unexpected.

I use that to push my ideas – by tapping into the programming that entrenched a particular narrative in your mind, and then being able to hack the ideas forming that familiar narrative, so central to that belief.

It is a way in which to surreptitiously introduce your message, using existing programming through more familiar narratives.

The country has changed; I think everybody has changed, and they were ready for new stories. So, it becomes very important in my work – my sculptural work – to disrupt your experience of the lived world. Reality as you think of it – you stumble upon an object or a situation and become the hero in that experience, and it is intended to disrupt your perception of reality and open you up.

It becomes about other ways of thinking. That also plays a big part in the sense of the work being from another place, and not of this world.

It is a moment to welcome back to the port city of Jeddah new congregations of ideas and to begin

to cement something fluid. Importantly, the biennale is not for art. It is the nature and narratives of our lived world that we are there to ask questions about.

Visit muhannadshono.com and follow @muhannadshono on Instagram.