Manal Al Dowayan has a way of explaining what she is doing with an assuredness that amplifies why she chooses her art over everything else. She openly speaks about how her father wanted her to pursue other ambitions, which she managed admirably for many years, until her creative urges got the better of her.

Now established, Manal sees herself not just as an artist, but also as a facilitator inviting communities of people to contribute to their own cultural narrative. An example of that is Oasis of Stories, an exhibition that is part of the AlUla Arts Festival. It comprises a kaleidoscope of ink drawings that chronicle the individual interests and aspirations of the young and old alike.

For Manal, having found her voice, this heart-warming exhibition is about allowing others to speak and to express themselves on paper, with words as well as pictures. The simplicity of the idea, as an invitation to all, is fundamental to Manal’s way of thinking – that she speaks not just for herself but listens to what everyone has to say.

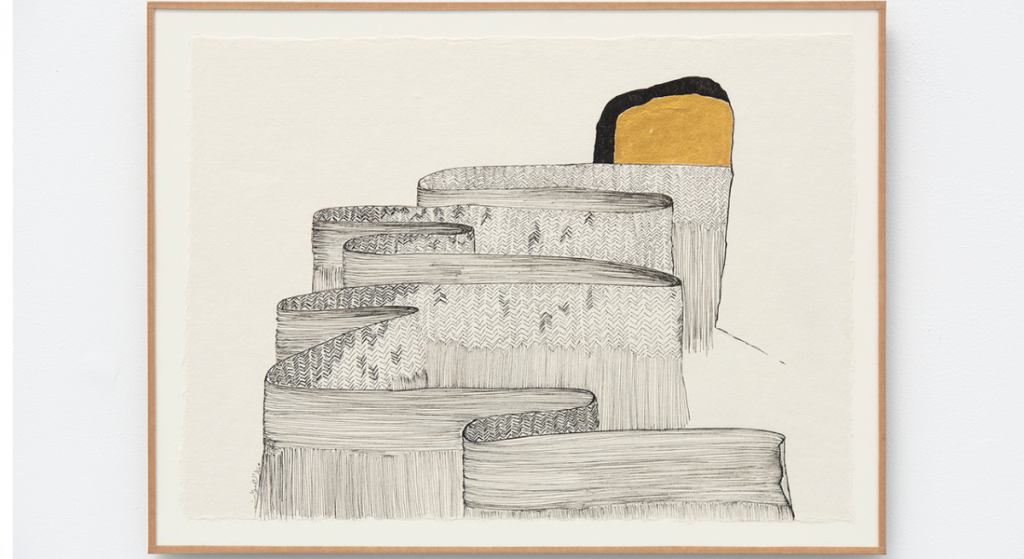

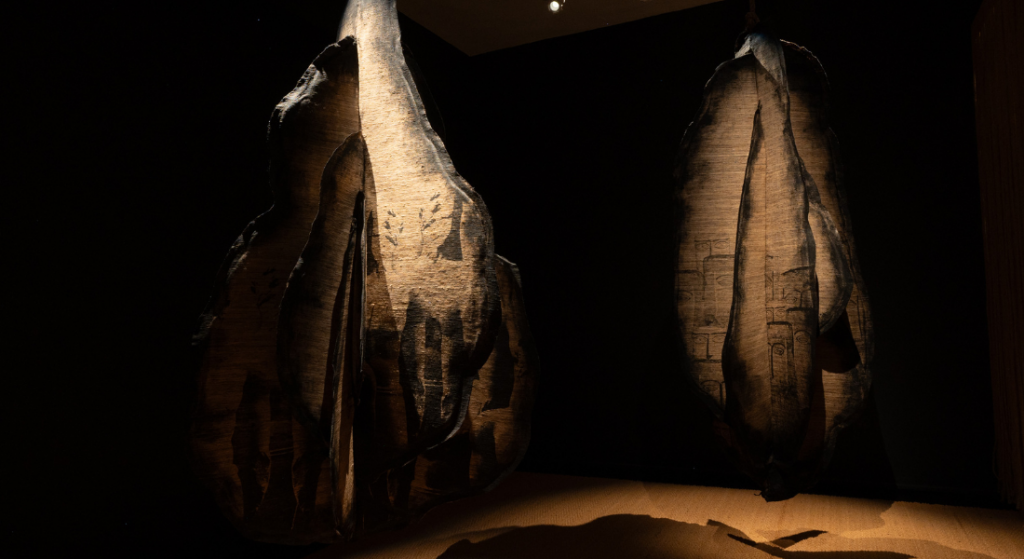

From the modest to the equally meaningful, Manal’s exhibition Their Love is Like All Loves, Their Death is Like All Deaths in AlUla has been created in collaboration with the Sabrina Amrani Gallery in Madrid, filled with works that draw on the traditions and tapestries of the Kingdom. Between both, Manal appears in her element.

Here, the words and the pictures were not private, but for public purposes. You know, I’ve been doing participatory work as part of my practice for many years. I can go back to the very first collection of work I ever did, and I’ve asked people to do things for me that I wouldn’t do – for example, come and pose for my photographs. I don’t like to be photographed for my own artwork; in fact, I hate being photographed.

Also, for a few of my projects, I did ask women to draw for me, for the Tree of Guardians. I didn’t draw back then; I started more recently. I have started drawing in my studio but never exhibited this in any of my gallery shows. This is probably the first time I have exhibited my own drawings. If you see the ones with ink on paper, for me, I see drawing very differently. So, when I proposed to someone to draw something for me, I wanted them to express themselves in whichever way they wished. I was also very open to them writing as well as drawing. So, you have a lot of poetry in the exhibition.

I invited people to trace their hands, so there were a lot of hands, which triggered others to ask for more paper and want to do something more imaginative. You saw some drawings made up of very basic scribbles, but I wanted to accept everything. The most important thing I told them was that art is about expression, not perfection.

I want them to love it. I want them to say, ‘This is mine.’ When you arrive as the audience, I’ll want to show you something, to be able to blow your mind. This is my grandfather’s struggle, and this is my heart. I want that kind of connection. Public art is something we have just now started making in Saudi Arabia. My first-ever public commission was Desert X 2020, which they acquired, and is permanently here. A series of trampolines entitled Now You See Me Now You Don’t, it sits at Habitats now. But before that, it was the first thing I put into a landscape and within a community, and I’ve been thinking about this idea of public art since then.

We know how to read and interpret, and we know how to connect the artwork to the real world, because we’re trained to do that. But how do we do this with something that arrives from somewhere else? I developed a work in the North Pacific triangle in Japan, and it was a crisis for me – what was I going to do, placing an artwork in one of these communities? I was invited to Buka Island, a small fishing island. I didn’t want an artwork dumped there without it having any real connection to those living there, so I thought about creating a work that drew on their traditions of fishing, coming from the Gulf where we have it as a crucial part of our lives as well. We have a heritage here of singing traditions by women who used to do things in the sea, to protect the men to come back, and I took those songs and traditions and brought them to Japan, to this fishing community. Then we exchanged songs that women sing for their fishermen when they go out, to protect them and bring them back. So, it’s a very complicated journey for me, of the public and the private, and not all artists need that journey; this is just my style.

I think my life has been a journey because I never went to art school to start with. I have contemporary art certificates from my time at the Royal College of Art in London, but when I started, there were no art schools here in Saudi Arabia, or any kind of arts economy or gallery exactly. When I told my father I wanted to study art as my passion, he said, ‘What will you do with this degree?’ He added, ‘You will struggle.’ Even I couldn’t see, with my own eyes, what a female artist would look like here in this country. It was something that I just felt I needed to do.

I studied computer science to the Master’s level and was on the Dean’s list the whole time, for my father, but at the same time my mother would give me money in envelopes, not through wire transfer, for art classes. Anybody visiting the United States or coming to London when I was doing my Master’s would bring more envelopes from my mother. I would then register in classes at Central Saint Martins, and that was my art education.

I felt I was able to be more instinctive. For example, what I have done in the community in AlUla now is called participatory art, and it has a science around it. Art critics and scholars write essays about ‘public art’. There’s an art history canon, a Western perspective that emerged in the 1960s and ’70s when it all started. I didn’t know about any of that; I just applied my own instincts. But still, you have to define it within this canon, and therefore I call it ‘participatory art’.

The Whitechapel Gallery sells a book of edited essays, there’s one about participation. I remember buying that book when it was first published, and I thought, ‘Oh my god, this is what I’m doing now.’ Philosophers and sociologists have explained it, and there are artists and galleries that have tried to explain it as integral to reclaiming the public space, but it wasn’t useful. It’s actually about cooking; it’s not about just making art, but about the politics of authorship. When I made this work, it came from a pure instinct for wanting to do something that I just feel I should do it this way.

Without art schooling, you think more instinctively. As such, you will never see any of this ‘art speak’ in my essays. I write all of my artist statements on my website. The language is very simple.

I went to the Royal College of Art when I was already an established artist collected by museums. Yet, I still had a desire to study because I was working within a certain style. I wanted my work to have a moment, because the art market and curators were asking so much of me. They wanted more and more of my work, so I needed to be able to detach to create a new series of work.

At art school, when I would write my artist statements, my professors would say, ‘Get to the point and say what you want to say.’

I would always argue that the system was entirely Eurocentric and that it didn’t want to understand my way of expressing myself

When Arabs speak and write, it is decorative; we are trained from childhood to understand to read between the lines. This is in our DNA. If I read a poem, I will know that this person said he wants to kill someone he knows, or that she loves something incredibly. We express ourselves more instinctively.

Visit manaldowayan.com and follow @manaldowayan on Instagram.